As a rule, I can’t relate to landscapes. Oh, I like them as elements in films, like in Antonioni and Barry Lyndon, where they make their statement and then go away so I can look at people again. But when someone puts one on a wall for me to look at, my mind wanders. I know this reveals my lack of sophistication. I recognize Turner’s genius, but after a while all those yellow explosions sort of blend into one another, for me. As for the traditional stuff, Constable and the Hudson River painters etc., forget it.

I had less trouble with the photographer Robert Adams’ big show at the National Gallery, maybe because I had help. The show has gobs of signage explaining the phases and development of his work. While I’m usually suspicious when the verbal case-making in these shows gets so lengthy that it’s trying to do the artist’s work for him, this was pretty well-spoken, and it helps that Adams himself wrote beautifully about his own pictures and a lot of that is included here.

The curators tell us how Adams started out in Colorado with a sort of mystical bent, a “conception of nature’s gift — its beauty and the peace it inspires in us,” and sought to find and show “the silence of light… a quiet so absolute that it allows one to begin again, to love the future.” Big dreams, Bob! But I say he pulled it off. There’s one interior of an adobe chapel, for instance, in which the hand-molded window glows with ghostly sunlight while the rest of the room, but for white gleams on the rails of the pews, remains sepulchral and cool; this is gravity and simplicity to rival the grandeur of a cathedral. A child’s crudely-lettered sandstone grave, a painted brick movie theatre, great spreading fields, a dusty street that reaches toward, in Adams’ words, “an expanse so empty that it can almost seem to spin” — it’s all simultaneously modest and splendid. One might call it Mere Photography.

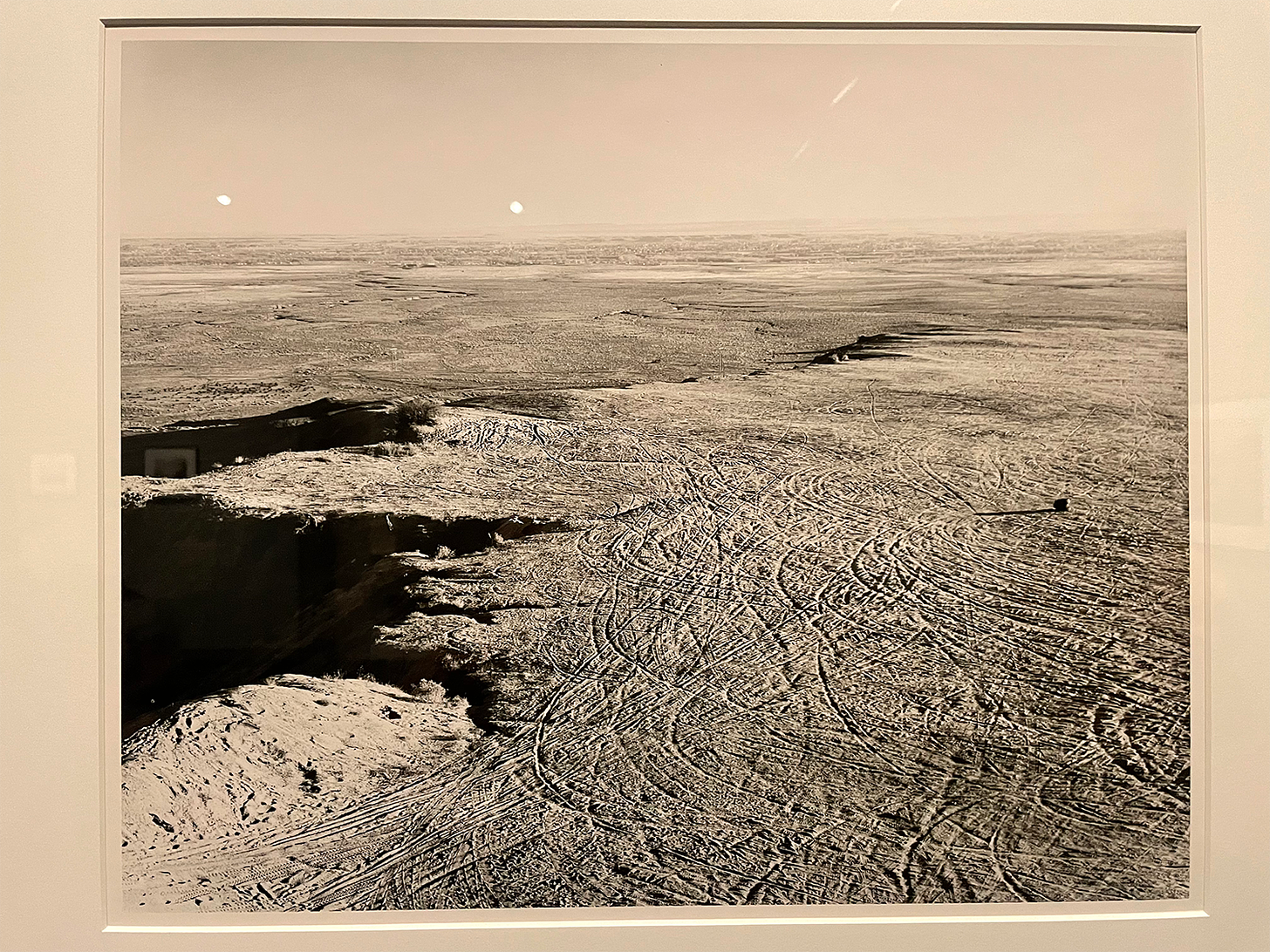

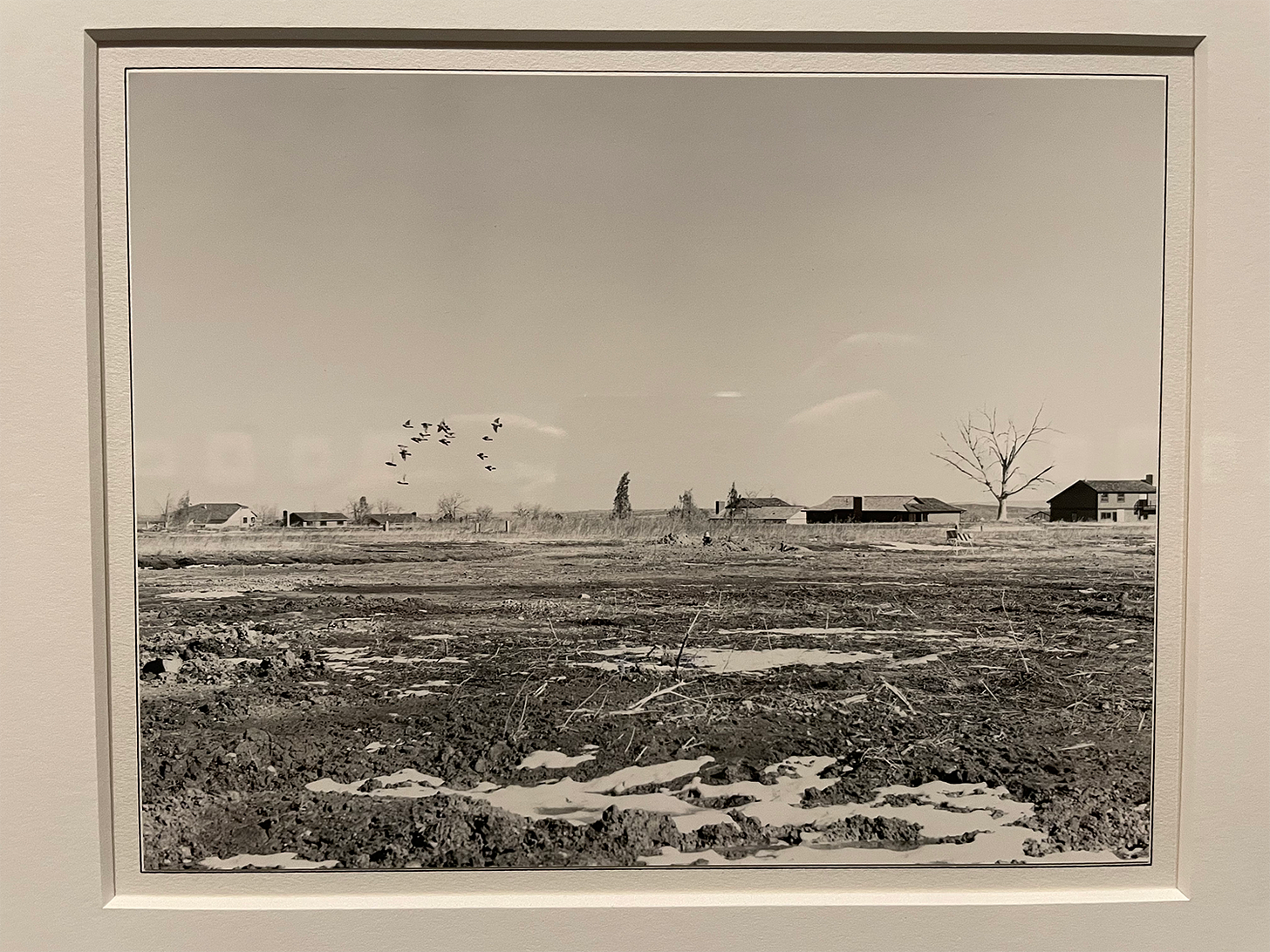

But over time not only Colorado but the whole west got scraped and overbuilt and clear-cut, and Adams wondered — again, his own words — whether “the big views, the ones you instinctively associate with the word West, [had] been eroded to the point where there is no grandeur left.” So he applied his gift to other approaches. He detailed the cuts and scars of progress, which still had starkness and scale — like the disused orchard that collapses into a ravine, or the chewed earth around a burgeoning housing development.

At one point, allegedly alarmed by the threat of nuclear devastation, Adams hid a camera behind grocery bags he carried and went around taking pictures of the inhabitants of this new world — who are just people like us, of course, dandling infants and waiting for rides and doing what they did before things began to change. The Adams book they come from, Our Lives and Our Children, sounds a bit much — “the final pictures show people looking over their shoulders or up into the sky with great alarm, as if they were witnessing a cataclysmic event.” Yikes! But the photos out of that context are eloquent, and the furtive camerawork, sometimes blurred and often off-center, carries a hint of desperation.

But there isn’t much of that. People, I mean. When you see other Adams pictures from that same era — a carnival ride at night gleaming like a fluorescent jellyfish, a front yard and house and, in the window, a tiny silhouette — you may wonder why, since he clearly went among people, he went out of his way to avoid photographing them. Maybe, one extrapolates from the work, he came to it not only out of a mystical vision but also from great loneliness, or at least a guardedness about his solitude. He wouldn’t be the first mystic like that.

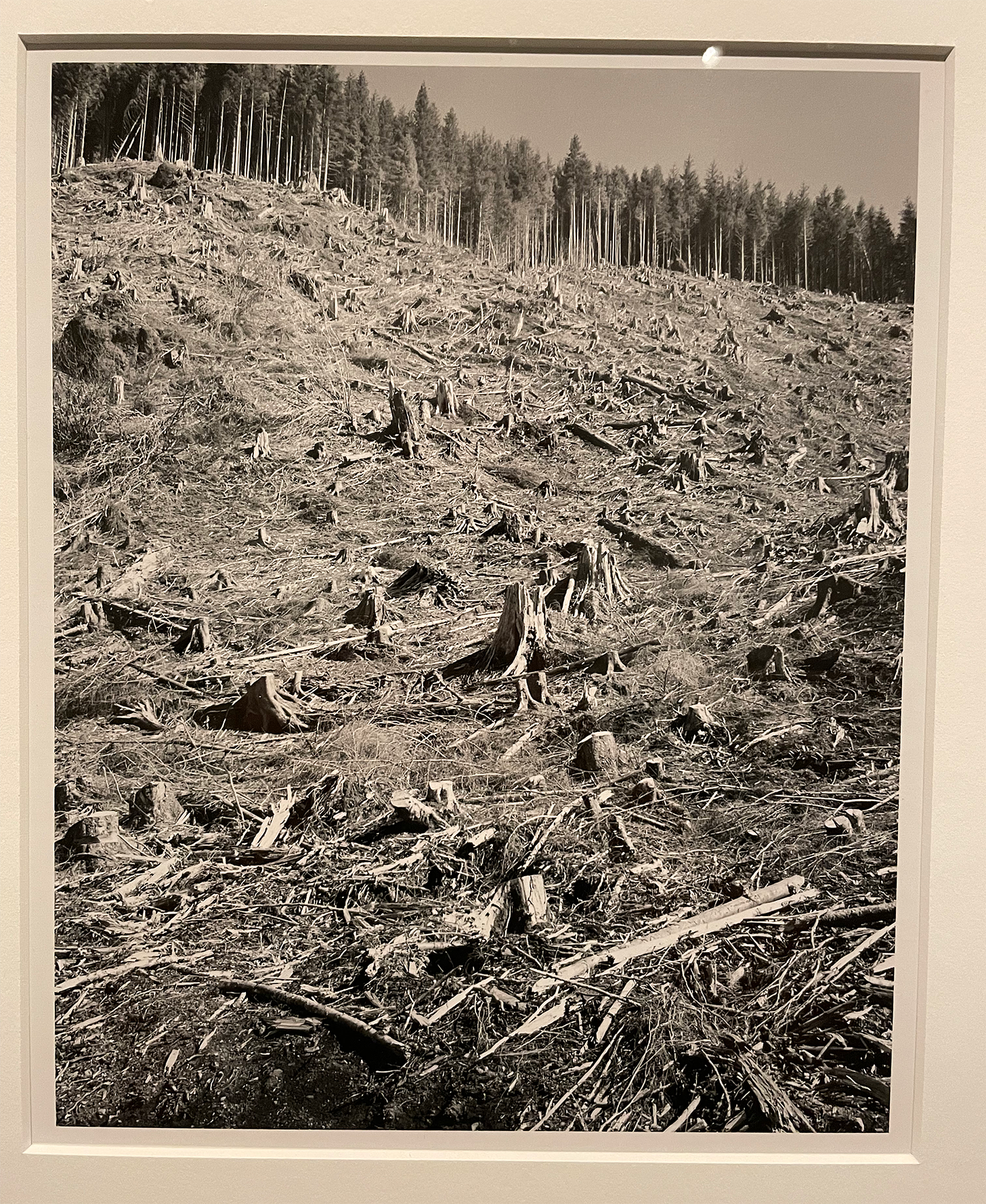

By the end, you get a sense that Adams is fed up, whence comes his money quote, suitably amplified on a gallery plinth: “After people live awhile in a place to which they’ve laid waste, it gets to be easy to hate a great many things.” But his late photos don’t really feel condemnatory. For one thing, the show’s final gallery has plenty of normal beach and seascapes that, while the ocean fog may have been meant to look ominous, seem to take the available beauty for what it’s worth; there are even a couple with people in them, though they are facing away and one woman is taking a cellphone pic. And the giant ruins, like the awesome one that seems at first to be some sort of rough abstract pattern, only to eventually reveal itself as a large field of torn stumps, are not indictments, entirely — nothing so direct or paltry. There are all kinds of reasons and ways to be fascinated by destruction — there is the adolescent, horror-movie fascination, for example, but there is also, especially if one has lived a long time, the fascination with what this world we thought — no, knew — contained something eternal, if only in spirit, could be so brutalized and still be the world, still support and hold us.

"a carnival ride at night gleaming like a fluorescent jellyfish"

This new month is barely 7 hours old and I got my 7 Bucks worth!

On one hand there is the honest insightful criticism /comment on art, film, music, literature. On the other, brutal takedowns of Republican assholes.

This is truly a full service substack.

Tasty. Gotta see this. I'm a believer that the witness of beauty is one of humankind's best endeavors, and here's somebody witnessing where he finds it, in all its contradictions.