Sometimes it’s the little things that bug me. It may be that I’m able to see a World in a Grain of Sand, or maybe I’m just persnickety. See what you think.

It’s about this tweet from early in the week, pictured up top, by screenwriter Jeff Sharlet. A.O. Scott, the lead movie critic at the New York Times, published a year-end top ten, and “@jason,” aka Jason Calacanis, whose large Twitter following is apparently based on an entrepreneurial pitchman/gasbag routine, bitched that he’d never heard of the movies Scott cited and where’s Top Gun Maverick, and Elmo emerged to declare film criticism “woke.”

I was slightly surprised when people in related discussions were sort of on board with the basic idea: namely, that because critics (and members of the Motion Picture Academy) favor movies that are obscure and not likely to be popular in the Great American Multiplex, their judgments are somehow illegitimate — either because they are, for some perverse reason, unable to enjoy and celebrate the glurge that average suburbanites consume with their tubs of popcorn, or because the very idea of critical expertise is illegitimate.

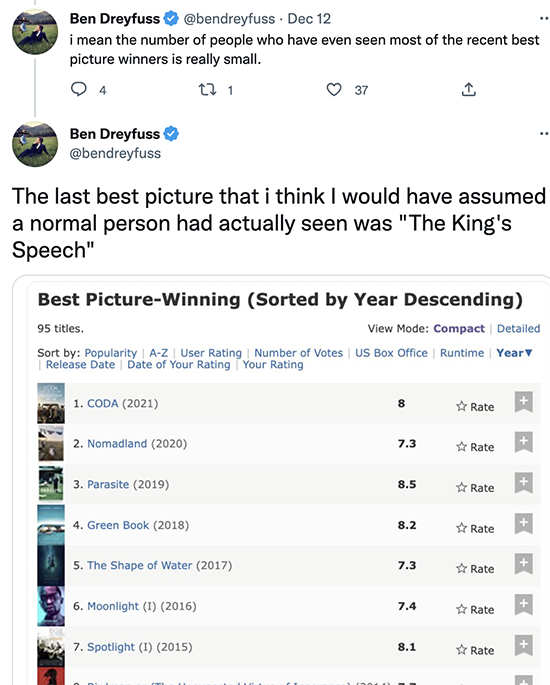

By and large these are not worth hunting down and quoting verbatim, but I will reproduce this one from that oddball Ben Dreyfuss:

As was widely noted Dreyfuss is wrong on the facts — even Parasite and The Shape of Water, weird as they may seem to some people, did fine at the box office — but the idea that the swells are trying to put one over on the Common Man with their fancy movies is observably common.

Adding piquancy to the whole discussion is the background of most modern critics, who are steeped in the legacy of critics like Kael, Farber, and Sarris who were crazy about the popular old Hollywood movies, and disputed the hierarchy of genres accepted by most non-film-critic intellectuals of their time.

But it’s not even any honest dispute between popular cinema and elitist cinema, or popular anything and elitist anything that bugs me. Some people prefer McDonald’s; sometimes I do, too. What bugs me is sort of what used to be called reverse snobbism, though that term doesn’t quite get at what’s so obnoxious about it.

Most of us know reverse snobbism from its relatively benign social forms — for example, the well-bred educated young person who hipsteriffically slathers themself with downscale dirtbag signifiers like cheap beer, a gimme cap, and cheesy music choices. This has in a few senses become a wider cultural trend, which I detect any time brights and swells affect tough-guy argot; but since the inventive use of language helps keep it lively I will not say them nay.

But this tendency has fed our culture in another way and I think it dovetails with some of the negative political tendencies I usually write about. We might call this weaponized reverse snobbishness — the idea that someone who approves and endorses the high-toned stuff is not just wrong, but needs to be strenuously bullied because his opinion is not just an opinion but an existential threat.

Now, you know if Elmo were, say, served the kind of inferior chow or brew that us lowlifes subsist on, he’d certainly throw a shitfit — so his putative populism is not, you may be sure, based on an honest personal preference for the cheap stuff. What he’s protecting is the branding of the cheap stuff as something Real People like — so that he, rich and unreal as he is, can associate it with himself, and thus be considered popular.

It’s like when the Republicans portray universal health care and the popular vote as “elitist” preferences — even though polls show those things are favored by a majority of Americans. They’re not being populists by supporting the popular choice, but by associating their own policies with signifiers of popularity — usually with tough talk, declarations of patriotism or police worship (things that were popular in the heyday of their rapidly-dying older adherents), and/or by declaring anyone who’ll admit to wanting the actually popular thing is really part of a despised minority of wonks, snowflakes and socialists.

I doubt either Elmo or Calacanis has a strong feeling for aesthetics, or even for movies, at least beyond whatever momentary synaptic glow each associates with whatever’s happening on the screen in front of him while he’s getting his dick sucked. But they do know that their rackets rely on projecting total confidence that anyone who’s a real person sides with them, and anyone who doesn’t is fringe.

That’s why Elmo had to make it obvious with that weird association of “wokeness” with classy movies — part of his populist positioning is that he’s the opposite of woke, and therefore associated with all the cool and popular things that go along with being anti-woke.

That’s why he got Dave Chappelle to bring him out onstage in San Francisco last Sunday — because he thought the comedian, being popular and rude to trans people, was a suitable complement to his own shtick, notwithstanding his lack of any equivalent talent.

Elmo may not have expected the ten solid minutes of booing he received at the Chappelle show, but his response to it — claiming it was only because the audience was all “unhinged leftists” — was completely expected. In fact every living American could boo him at same time on a coast-to-coast hookup, and he would insist the majority of each living American’s heart was, despite the treason of their lungs and vocal cords, on his side, and his incels would eat it up.

And if, as seems very possible, Elmo’s current outrageous mismanagement of Twitter winds up either destroying the company or obliging him to relinquish it, neither would that call his approach into question; it would just mean that Twitter had resisted his anti-woke rehabilitation efforts, rendering it woke and thus on the wrong side of the only public opinion that matters — the one he bought.

In fact you could say that’s why he acquired Twitter in the first place — with its millions of voices (albeit representing only a fifth of Americans, and its loudest voices representing only a tiny sliver of that) it provides a pretty fair simulacrum of the vox populi — and it’s totally within his power to distort. It might remind you of Tommy and the mirror — were there any evidence that Elmo has ever experienced a moment of self-examination.

It's absolutely true that Musk is trying to wrap himself in the mantle of the Common Man, embracing all the conservative assumptions about what the Common Man wants: “Fuck your universal healthcare and access to the polls, I want to watch Tom Cruise blow things up while I die of a treatable disease, Wokesters.”

But I find the most tragi-comic – and maddening -- thing about Musk to be his fans. When I look at what’s happening at Twitter, I’m reminded of the tried and true comedic premise of the protagonist who can never admit he made a mistake: he never course-corrects, his every new blunder generates an accelerating level of chaos, until finally he’s standing in the street after setting his own house on fire, loudly proclaiming “I meant to do that.”

Except in Musk’s case it’s his fanbois who are saying it *FOR* him. In a month, if the only things remaining at Twitter are Elon himself and a mainframe computer the size of a bowling alley, and he has to run an extension cord to a neighboring building because nobody paid the electric bill, his fanbois will STILL be saying “he meant to do that.”

I’m already tired of Musk. He’s so predictable, as if a TV series writers’ room was told their show needed a rich, unselfaware asshole character and they decided to toss in every cliche they could think of. To me the more interesting part of Roy’s essay is the question, “What is the right standard for good art?” How many people get to see a movie depends on a lot more than its quality, like the luck of the draw of opening weekend, or how much PR was pushed early on, so that’s not a reliable measure. I’m reminded of a back and forth in high school art class, where we were exposed to representative examples from centuries of painting in the hope we would take away a lifetime of appreciation for how art (or artists) work. To a student’s objection that he already knew what he liked, our teacher replied, “You know what you like, but do you know why you like it?” I haven’t looked at a painting, watched a movie, read a book or listened to music since then without hearing that question in the back of my mind. I doubt Musk has any idea why he likes “Top Gun” more than “Coda,” and why the latter has more to say to him than the former ever could.