Pandora’s AI

A chain reaction that might destroy the entire world

We — by which I mean people who are not insane — talk a lot about AI as a growing menace. Despite the glibly optimistic techbro pitches, it is not at all like the internal combustion engine or personal computing — those were meant to relieve humans of effort, not to relieve effort of humans. I’ve written a few times about how this tech pushed on us by rich fucks and scamtrepreneurs is not merely crummy, but designed to be crummy, because the goal is not to be good, but to be cheap and lucrative.

It can be admitted there are some functions for which AI is well suited, such as fraud detection and other areas where the involvement of human intelligence is not important. But it seems like a mistake to even admit that much, because the pressure to accept the stuff is so great that every point granted seems like a new beachhead the grifters will seize and crawl over to get at us.

A year ago, whenever I saw AI actually applied to intellectual and creative tasks like journalism and literature (and the freakish AI-generated imagery by which most people know it), the results were so facially bogus that I never thought a consensus would develop that these nightmares were promising, positive developments.

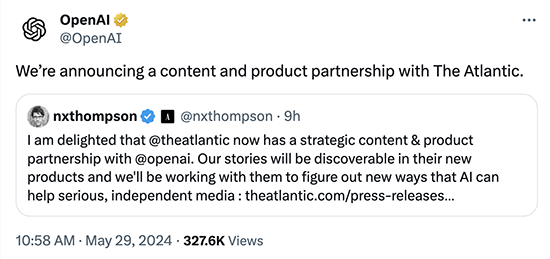

I guess I was just inattentive, because some people have been doing it for years — like The Economist in “How AI is transforming the creative industries,” dated April 2021. Also, in the Age of the Algorithm, consensus, or at least something that looks like it, can be forced for even the most repulsive propositions. Elon Musk’s xAI — talk about two tastes that taste bad together! — has attracted six billion dollars in capital. In the popular press I see stories like “Future-Proof Your Career: 10 Essential Steps For Thriving In An AI-Dominated Workforce” (which sounds to me like “How to Make the Most Out of Life in a Fallout Shelter”). And lol/ugh, this:

In “Memo to Hollywood: AI Is a Threat — And an Opportunity” in the Hollywood Reporter, “power player Dawn Ostroff” tries to strike a conciliatory tone. She accepts that people worry about “the threat to our creativity and thereby our humanity itself.” But I don’t think Ostroff means by that what most of us do. We see a threat to humanity and creativity because the champions of AI seek to replace both humanity and creativity with the bilge that comes out of their new toy. But because Ostroff is a power player in what’s known as a creative industry, she sees it as a turf war, in which the artisans balk at an AI-assisted reduction of their market value, and management negotiates from position of strength.

For a while Ostoff talks a good game about “the creative process” as “an integral part of our collective human experience” etc. But after covering cave paintings and clay tablets, she jumps over thousands of years of the lively arts to get to, as it were, the fun part: Science-fiction movies.

Think of Arthur C. Clarke’s 2001: A Space Odyssey predicting sentient computers or Ernest Cline’s Ready Player One imagining the Metaverse and Spike Jonze’s Her exploring the outrageous idea of computers as our companions.

Yeah, yeah, I know, but here’s the part where my blood really started to run cold:

But let’s remember that the computer was originally invented by Charles Babbage to automate mathematical calculations that were previously computed by people.

Not too much of a leap, right? People used to do the grunt work of computing, and now you nerds sweat over screenplays and light readings. Isn’t your toil exactly like that of ancients at their abaci? Wouldn’t you like a hand with that?

If so, Ostroff knows where creatives can get it — from “our colleagues in the tech industry.” In the past these colleagues were inspired by “our fantastical stories about life in the future,” and so “set about making those worlds a reality” — you wrote the stories, they did the CGI, we all made money! Heretofore creatives have been in the driver’s seat, but Ostroff suggests it’s time for someone else to take the wheel:

Did writers who imagined a science fiction future truly believe it could ever happen? Did engineers believe what they were reading as science fiction could be a reality? Who knows? And yet, here we are, taking those stories even further than ever imagined. We envisioned it, and then they figured out how to build it. And today, we have machines being the creators — coming up with ideas, stories, art, music and other forms of creativity and imagining a new future. This is certainly revolutionary, and in many ways, very difficult to comprehend.

I’ll say!

This is gibberish, but to a purpose; the things Ostroff wants you to take away from it are 1.) Creativity is a wonderful thing, 2.) and so we shall, with furrowed brows, consider “critical questions about the future of human creativity and innovation” but 3.) in the end you really don’t have a choice:

We’ve been at the brink of existential threats before. And while our imagination and creativity often brought us there, it also brought us back. Finding the ways to use AI to make us better at what we do is the path best chosen. Otherwise, AI will do it without us.

That is not true. AI is not doing anything “without us.” AI could be hyperdeveloped to an infinite degree and still stay safely dormant in its box, like a world-killing weapon decommissioned by common consent, and there’d be an end to it. It’s strange to remember how we worried all those years that the nuclear genie would be unleashed, had to be unleashed, because we assumed our leaders’ lust for power was so intractable it would drive them to kill us all. Who knew the far greater menace was market opportunity?

Eee-yikes. Aside from costing real people real jobs, the incredible idea AI can (or should) replace human creativity is a high tech fantasy similar to the theory that a thousand monkeys sitting at a thousand typewriters for a thousand years would eventually produce the works of William Shakespeare. They would not, but even if they did Romeo and Juliet would each have 11 fingers.

Meh. I'm not worried about AI because the actual facts on the ground show that replicating the human brain/mind is impossible, and also because what is being palmed off as "artificial intelligence" is really just Large Language Model computing--it's not capable of creating anything, it can only parrot and recombine that which a human has already thought and written down.

Cast your mind back to just 5 years ago. Remember when self-driving robotaxis were going to be all over town? What happened to that? Well, it turns out that driving a car is an incredibly complex endeavor, and it relies way more on human intuition than than anything you can program into a computer. (For example, you as a human can tell just by looking at someone's face and stance whether they're about to step off the curb. No computer can do that.) RoboTrucks are encountering the exact same set of problems even though the task they're being assigned has been reduce to the bare minimum of "pick up here, drive three miles, drop off there."

And the creative products AI produces are, at best, pathetic. And for the same reason: No computer can mimic the human mind and its intuition/peculiarities.

So Hollywood and publishing are all excited that AI will finally rid them of these meddlesome writers? And they can at last simply pay the electric bill and rake in the cash? Well, I have a Juicero here that I'd like to sell you. Barely used! No? How about a Theranos blood sampler?