Ragged but Right

Slap Shot is what was cool about the 70s

I knew a comedian some years ago who used to refer to the 1970s as “The Age of Unprotected Anal Sex.” While I wouldn’t say that nutshells it, it does carry a good deal of the vibe, and I’m not talking about the pre- safe-sex angle, though that figures in as well.

A lot of people who didn’t experience the 70s talk about them as if they were some sort of wild free-fire zone of decay, corruption, and schmutz. They’re like the guys who talk about how scary it must have been to live in New York back when there were poor people in Manhattan. “The gloomy backwash of the 70s is perhaps best memorialized in the nihilistic and existential tone of so many Hollywood films of the era,” says some guy born in 1967.

I mean, he’s not totally wrong, but I think something most of these people miss is that the 70s were also a lot of fun — a lot more fun, if I may say so, than a lot of people seem to be having right now. And part of the reason was a general laissez-faire approach to… well, everything.

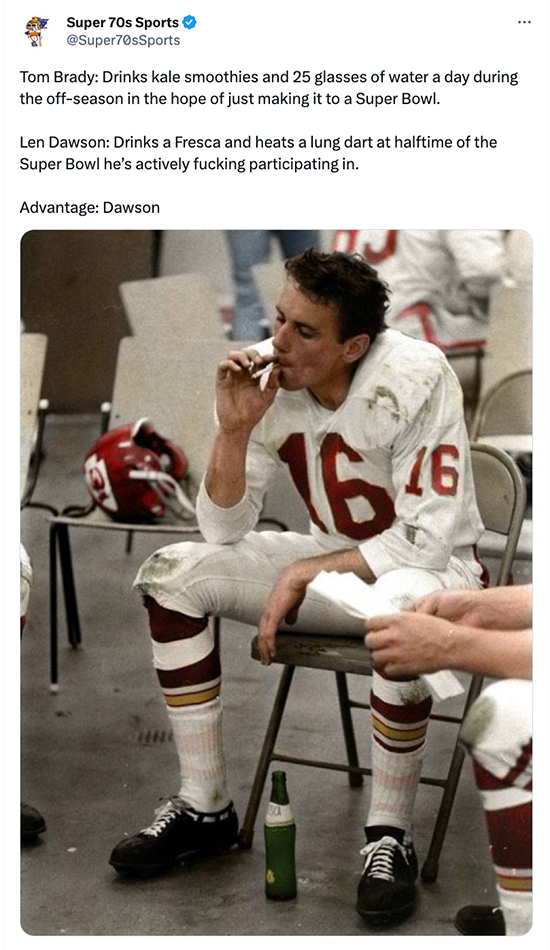

I actually think one of the guys who has a better-than-most bead on it is the owner of the Super 70s Sports Twitter account. He’s crude, and cavalier about the violence, disregard for personal safety, and general failure to give a shit that for him distinguishes the decade. Get a load of this:

One can go too far with the nostalgia for 70s crudity, for sure. There has been some beef about the excision of some racial slurs from recent editions of The French Connection, which I understand and with which I even sympathize. But it’s not something I’d go to the wall for because, for one thing, The French Connection ain’t exactly Lola Montes and, for another, whenever something like this comes up, I notice, you can very easily pick out the guys who are sincerely dismayed by censorship from the ones who are just mad that one more set of racial slurs has been removed from the world.

In a way this is a very 70s way of looking at things — making allowances, and not mistaking some little aesthetic slap-fight for reality writ large. If you can’t exactly square your moral judgment on one of these things with the vast GE College Bowl debate about oh you say you’re against censorship well what about blah blah blah, the appropriate answer is go fuck yourself.

Speaking of Super 70s Sports and laissez faire, I finally saw Slap Shot last weekend. (It’s on Netflix!)

I don’t want to make too much of it. In fact not making too much of it is a 70s thing, too. It’s a fun movie by the not especially brilliant George Roy Hill (though the especially brilliant Dede Allen, who gets her credit immediately after Hill’s, probably has a lot to do with its scuzzy brio). And it’s far too loose and discursive to even pretend to carry a moral or message. But it does have something resembling ethics.

You probably know it’s about the Charlestown Chiefs, a loser minor league team in a dying mill town. You’d think the story would be grim and in some ways it is — every once in a while we get a good look at the smokestacks pumping soot into the air, and we also know when the mill finally shuts and the smokestacks stop the real dying begins.

Aging Chiefs coach Paul Newman is pissed about that, and so’s the college boy on the team, Michael Ontkean, to whom Newman relates and even gives respect despite the kid’s Ivy League pedigree. (There’s another long-dead legacy of American popular art: The idea that a college boy and a working-class Joe would have anything to say to one another.)

But Newman slowly awakens to an angle. He’s always working angles, of course — he’s a smart blue-collar guy, if he’s not working angles he’s dead meat, and how then could he be our star? He’s working them as well on his not-quite-ex-wife, Jennifer Warren, who is sympathetic but not going for it — but his teammates are much dumber, and Newman decides to play them (innocently enough — it’s good for their morale, see, and hell, maybe even for that of the town, not to mention his own future prospects as a coach or maybe front office guy) by planting a story with a local newsie that a big company wants to buy the team and take it to Florida if they start winning.

(The easily-played sportswriter is one of Slap Shot’s many lovely grace notes; when Newman, buttering him up at a bar, praises his poeticisms about “bright colors of their jerseys flashing against the milky ice,” the scribe, still in his work suit, says sincerely, “Well, I try to capture the spirit of the thing, right.” I have to say, I felt seen.)

There are all kinds of subplots and complications. For one, Ontkean’s wife, a very young Lindsay Crouse, is sick of his whole act, and Newman keeps putting moves on her — though he’s not trying to fuck her (he says) so much as put her in the penalty box awhile because she’s a “champ” and he doesn’t want her to blow a gasket before whatever magic he’s working can fix her marriage to his golden boy. (When it does, it involves Newman’s ex doing Crouse’s hair and makeup so she looks like the rest of the hockey tramps, inspiring Ontkean to bare-ass terpsichore.) My guess is, had he not been too exhausted on game night, Newman would have at least tried, and I bet that was the consensus on movie night, at least among the males.

And then there’s the goonification of the Chiefs as Newman and his team realize the royal road to fan frenzy and media success on this circuit of forlorn factory towns is Broad Street Bully behavior. (It also makes them more likely to win games, since, it is suggested, this awakens their warrior spirit.) This gives us the Hanson Brothers, who are the focus of much Slap Shot fandom — they are, as Newman bluntly puts it, “retards” who play with slot cars, respond to every pep talk with the yapping enthusiasm of happy dogs, and just love to beat up opposing players even before the game has started. I can see why they’re fan favorites. They’re Super 70s Sports in idealized form: Shaggy, ugly, idiotic, dead game, and violent beyond even 70s sports reality. That they’re near-identical brothers just adds to the bro-y appeal.

It all goes a little off the beam at the end — which is also very 70s, because look, this is for the date night crowd as well as their loser friends who have to go stag, and they don’t need Aristotelian unities, they need some laughs and a little pep and a little romance. Oh, and it doesn’t have to be perfect — in fact, it can’t be, how can it be? Because this is filmed in a real Northeastern factory town, which is really dying, just as a lot of places were as the post-industrial, proto-corporate-raider mentality took hold. And that audience might be watching it in a bedraggled old theater doing two-buck double features (like I went to in those days) because the movie business was dying too. So it can’t be other than shaggy. If it were, wouldn’t the audience feel like they were being fucked with?

So the boys win the championship, but in the stupidest and most inglorious way possible (“Here’s your trophy, ya bum”); Ontkean and Crouse make up, but Newman and Warren don’t, though it’s an affectionate separation, with Newman still trying to con her (“I got a contract back there in the car!”). The mill town, with its unprepossessing little shops and dog statue in the park, is dying still, but the crowd still turns out for the victory parade and cheers their cheeseball heroes, and all are for the moment happy.

Because that’s how it goes, right? Sure, things are a mess — we all know the bosses don’t give a shit and we’re totally on our own, and any glory we get is a tainted substitute for the decent things we really deserve. But that’s no reason to bum out. The bar’s still open. I got some pot and a little pipe. If I get fired I can tell them to suck my dick and it’ll be worth it, at least until the rent comes due. And when it does we’ll think of something. Maybe I’ll meditate on some positive thinking tapes like Dave “Killer” Carlson (“You can get ‘em in any religious record store”). Maybe I’ll strip on the ice and make a mockery of the whole thing and still come up a winner. I got the contract back in the car. That’s the 70s, man. Until there’s no way there’s always a way.

There's a thing that happens:

Guys have some fun seeing how far they can catapult a pumpkin across a field

It becomes a contest

Guys, as they tend to do, start workin' the technology, medieval-style trebuchets are replaced with air cannon

Now the pumpkins are goin' over a mile, Punkin Chunkin' becomes a reality TV show, every team has a corporate sponsor

It's a process of Professionalization, Commercialization and at the root of it, Optimization (efficiency, maximization of results, high-performance, etc.)

Don't know why I thought of that, but it seems kinda like what turned the 70's into the 80's.

Slap Shot is a great movie! I saw it at the big theatre in the mall. It was the weekend. Crowded- everybody laughed hard the way you do when you are in a group and everybody laughs.

I have just been exposed to Ophuls the last year or two and I think Lola Montez is one of the best films ever.

Great essay. I had a lot of fun in the seventies. Way more than in the eighties.

The eighties sucked.