I don’t think my history teachers spent a minute on the Whiskey Rebellion. It was treated as a sidebar, something the early Republic had to deal with between major events and quickly move on from, like the Barbary pirates (send the Marines!) and access to the Mississippi (make a treaty with Spain!). In the rebels’ case — or so the impression was left me — they became inflamed by a justified tax on their beloved whiskey and rebelled (in my imagination, leveling muskets at revenooers, while occasionally sipping from small jugs marked “xxx”), requiring George Washington himself to ride out and chastise them, thus setting an example for other would-be hooligans until the Confederacy made rebellion a matter of Honor.

Well, you can’t teach everything, and the Rebellion was put down quickly and effectually so I can imagine why it was blown off. But I just read William Hogeland’s 2006 The Whiskey Rebellion and there’s a lot of stuff in there that’s fascinating, and some that’s gotten even more fascinating since it was published.

Hogeland tells the bigger story that many of you already know: Alexander Hamilton — not the admirable badass from the charming musical, but a mean political prick who we would now say was in the pocket of speculators like Jersey Bob Morris if he didn’t so cheerfully admit letting their speculations power his new financial system — sets up the first American excise tax, on whiskey. Whiskey is an important product on the western frontier of several states, especially Pennsylvania, because in those pre-greenback days it’s used as barter, and also affords an easy form in which to transport grain over the Appalachian mountains for trade. Worse for them, Hamilton’s system makes the tax much lighter on big distillers, who can take a flat-rate option and produce enough to make it pay, than on smallholders who cannot and must pay an onerous rate upon sale.

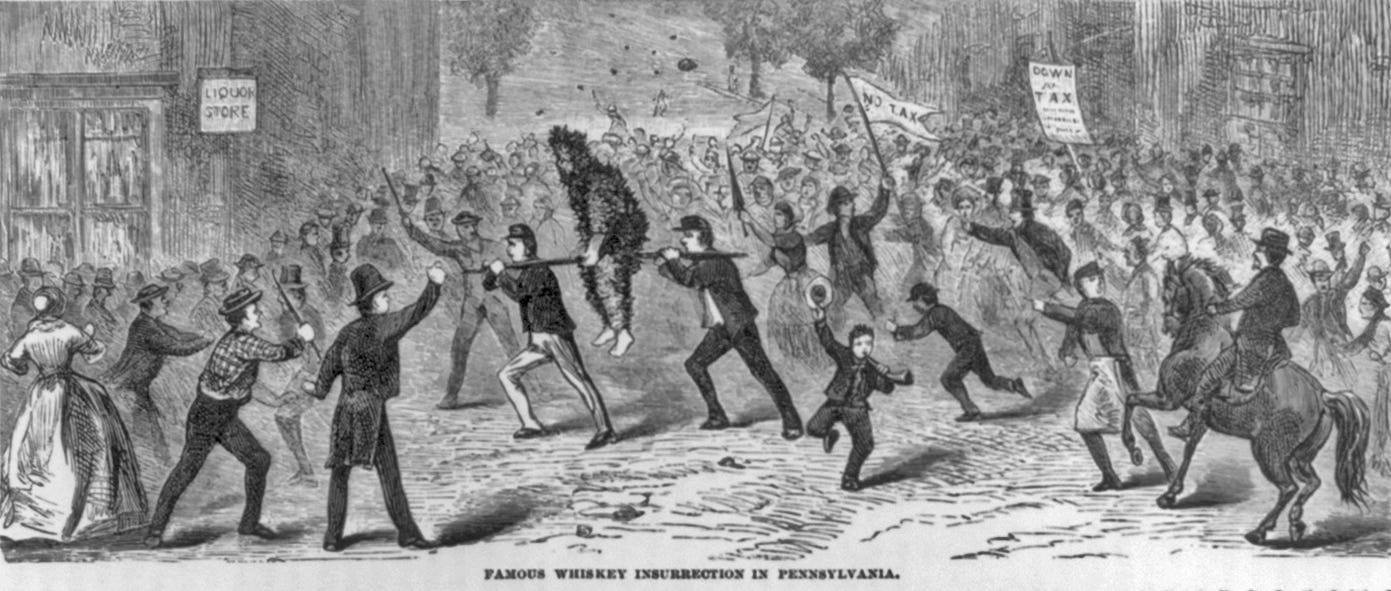

So some of the Western boys like the Mingo Creek Association start whipping and tarring and feathering revenue agents and eventually terrorize anyone who has aided and abetted the excise, and muster local militia in opposition to local law enforcement to keep whiskey untaxed. Things come a-cropper at Bower Hill, the home of revenue agent General John Neville, who has been issuing writs against the terrorists. Men are slain, prisoners are taken, and the rebels march through the frontier settlement of Pittsburgh — basically the urban center of western Pennsylvania — in a show of force and defiance after threatening to burn the place down.

Word gets back to Philadelphia, the nation’s capital, where Hamilton makes sure President George Washington sees things the right way — though the Father of Our Country, who is not only committed to strong federalism but also a speculator in Western land, doesn’t need much guidance. After a feint at negotiation, the feds march in and by sheer show of force cow such rebels as have not fled, arresting a few, including the fascinating mystic-political scientist-cartographer Herman Husband, who are all eventually released.

Hogeland adds some colors to this. For one thing, he emphasizes the precarity of the the new Republic’s federal authority by recalling the 1783 Newburgh Crisis, when on the cusp of victory in the Revolution Washington’s army threatened to mutiny over their delayed salaries until Big George pulled the famous almost-blind-in-the-service-of-my-country stunt. Hogeland portrays this as something very like a threatened coup engineered by Hamilton to get Congress to assume the war debt. (Bob Morris’ fat fingers were in that, too.) The U.S. in its early years was not a settled issue and, despite the fine talk of the Constitutional Convention, upheaval was not out of the question, especially when money was concerned.

Hogeland also lets us know how the powerful people in the new country were counting on westward expansion to make their fortunes — not least George Washington, who was always trying to make his western investments pay, and was pissed at his land agents for not more energetically pursuing leads and at squatters who worked his land without paying rents. (“The western land bubble,” Hogeland reminds readers, “would soon burst for everybody if lands did not appear to be under effective control of the United States government.”) Indeed, everyone who is not a rebel in the story seems to be actively planning to get rich on the settlement of the west.

Hogeland also gives detailed coverage of other key Rebellion players such as Hugh Brackenridge, a lawyer mainly known today as founder of the University of Pittsburgh and what’s now the Post-Gazette, who tried to play both ends against the middle during the Rebellion; Hogeland styles him an ironic figure who genuinely saw both sides but, due to idealism and irrepressible perversity, wound up alienating nearly everyone and barely escaped arrest and hanging. (“Rejecting, for all the obvious reasons, extremism,” Hogeland says, “he was both a federalist and a republican, a populist and an elitist. He therefore found himself perpetually at odds with federalists and republicans, populists and elitists.” A neo-liberal avant la lettre!)

One of the more dramatic passages in Hogeland’s story is from Hamilton’s investigation of Brackenridge at Pittsburgh, in which Hamilton confronts Brackenridge’s friend, Pennsylvania Senator James Ross, with a letter in Brackenridge’s hand, obtained by stolen mail, that appears to show Brackenridge in cahoots with rebel leader David Bradford:

[General John] Neville and [lawyer and Brackenridge enemy John] Woods waited eagerly as Hamilton read the note. Certainly it disproved the idea that the two suspects [Brackenridge and Bradford] hadn’t communicated. “What do you make of this?” Hamilton challenged Ross. “Is that not” — he made the Senator look at the letter — “the handwriting of Brackenridge?”

Ross knew Brackenridge’s handwriting, which was famously terrible. He read the letter carefully. After a moment he said, “It is the handwriting.” The Nevilles prepared to pounce, but after a moment Ross went on. “There is only one small matter,” he said. “The letter is addressed to William Bradford, Attorney General of the United States.”

Later, finishing Brackenridge’s interrogation and pronouncing him a free man, Hamilton tells him, “Had we listened to some people, I do not know what we might have done.” That ought to wash some of the powdered-wig preciosity out of your view of our Founding Fathers.

There’s plenty else, including such details as can be had — for 18th-Century frontiersmen did not leave behind the same sort or volume of testimony as swells — on the character of the rebels. These folks were, as you might imagine, more loyal to bonds of family and honor than to the, in their view, chimeric ties of the new federal government; a lot of these fellows had, as pre-Revolutionary “regulators,” defied British authorities who hadn’t answered their calls for assistance and justice, and they seemed to find the Philadelphia authorities similarly remote. It is notable that they were not averse to politics and helped return state legislators who made the 1776 Pennsylvania constitution; the Penn lege had at that time no upper house and, precociously, established voting and office-holding rights for the poor and landless, as well as legal tender laws that flustered Robert Morris — a document so radical that it actually made John Adams, in Hogeland’s paraphrase, “predict that Pennsylvanians would soon want King George back.”

The rebels were angry about the tax, but they were also at least somewhat inspired by the recent French Revolution, and they talked about bringing in the guillotine to deal with their adversaries. (“Word had it that David Bradford had taken to calling himself the Robespierre of the West.”) At the same time, they were also influenced by the Great Awakening and a view of Scripture that, while tending toward leveling and wealth-sharing, also somewhat reflected the loony medieval and prescriptive character of the temperance movement that came out of it: The rebels were angry at Pittsburgh mainly because it represented what would today be considered the “elite” — that is, people who could read and write and who practiced dark arts such as lawyering, and thus ran things. The rebels called it “Sodom” (Pittsburgh had then about a thousand residents and was not particularly known for licentiousness) and were only convinced to spare the city the torch when the city fathers agreed to exile some residents they were especially mad.

Reading Hogeland on the whiskey rebels, I share his interest in their maximal idea of democracy as well as his rejection of their weird Biblical taste for violence. (“For skeptical and penetrating discussion of how the local, spontaneous political action often prized by progressives tends to treat the rights of minorities and dissenters, see [Garry] Wills in A Necessary Evil.”) And it strikes me that, in a funhouse mirror way, the Rebellion was a sort of precursor of the rightwing insurrectionism we see now.

Sure, if you say “French Revolution” to today’s yobbos, they’ll denounce it as they’ve been trained to do by Glenn Beck, but you know if you gave them tumbrels and showed them rivers of blood, and told them the blood came from rich people they hated rather than the rich people they love, they’d be into it. And as I’ve observed in my coverage of religious-right gatherings in Washington, they also believe Jesus has sent them fulfill His mission on earth — which, as they see it, means: them in charge and their enemies murdered.

The sad thing is, the whiskey rebels never had a chance: The money was all on the other side, so they were routed and their potential political force dissipated, though wisps of it are still visible in various populist movements. Today’s rebels do have a chance, but only because they aren’t asking for anything that would cost the goons who goad them any money.

What if right-wingers had even one example to follow that wasn't violent revolution and 1776? Over here on the left, we can point to the labor movement, the civil rights movement, the gay rights movement, etc. whenever we need inspiration and a practical guide to how to get what we want. Nonviolent social change isn't pie-in-the-sky to us - we've done it, repeatedly, and we're doing it right now with BLM.

But over on the right? Where can you look as a guide to your own actions, or as a source of inspiration for a crowd you're trying to whip up? It's all 1776, all the time and... oh, wait, I forgot how they can also draw inspiration from the South's decision to start a bloody war over their sacred right to own other people as property. Never mind.

Thanks for the suggestion, Roy. I still had one credit on Audible this month and was wondering what to get.

In other news, I volunteered as a clinic escort/counter-protester at Planned Parenthood in Overland Park Kansas Saturday. Details here, if anyone is interested. We could use your help.

https://twitter.com/JoeMommaSan/status/1460055949029355522?s=20