Two of the many things I’m sure the Young People of Today know very little about are, first, the cult of Kennedy in the 1960s and part of the 1970s and, second, the repudiation of that cult in the 70s and afterward. (I refer to “cult” in the colloquial sense here, not the sort of thing where, for example, one’s deluded followers go into raptures when you demonstrate modest eye-hand coordination.)

Maybe some youngbloods who have read a little cultural history know that working-class Democrats, many of whom later turned tail for Reagan, actually had pictures of JFK on their walls, particularly in the years after his assassination. (Having grown up in a working-class neighborhood, I can attest to the phenomenon.) That was not a totally new development in American life; once upon a time citizens actually named their kids after U.S. presidents, particularly if they were poor and/or black. (One of our local charismatic churches has a pastor named Roosevelt McKinley Ford Jr.)

But these lunchbucket Kennedy stans came out of a new context. A lot of them were of fairly recent immigrant stock and their hero was the closest thing to an “ethnic” president the country had ever elected — at least he was to these Democrats, who remembered when Irish-Americans were considered goblins out of old Thomas Nast cartoons. Kennedy was also admired by non-white Americans, a growing piece of the Democratic coalition, and the parties’ divergent response to the civil rights movement pretty much meant than if you were at least sympathetic with that movement you’d probably be a Kennedy fan.

A couple of other factors contributed: The Kennedy PR machine was very professional and knew how to exploit their man’s mediagenic attributes, including not only his relative youthfulness and heroic war record but also his intellectual achievements (or pretensions, depending on how you looked at them). That may seem strange in our age of idiocracy, but when JFK was elected it had been less than 20 years since the passage of the G.I. Bill, and respect and hunger for education had (briefly, alas) pushed a little ahead of anti-intellectualism in the American psyche.

In fact, the handsome and poised Kennedy helped rehabilitate the “egghead” liberalism of his party, which conservatives had painted as effete and paternalistic, so that it seemed active and invigorating — as when he called for bold endeavors like going to the moon “not because they are easy but because they are hard” which was, you gotta admit, badass. Kennedy was rich, smart, optimistic, and energetic, and America liked seeing itself in him.

Then assassination stuck a halo on Kennedy, and when his brother suffered the same fate it just added to the effect.

I remember too when and how all this came apart. Partly this was due to political attrition: Americans got disenchanted with liberalism, even the cautious Kennedy kind, and lost faith also in their erstwhile go-forth-with-vigor avatar and his misty Camelot aura. The “death of the Sixties” wasn’t just about politics; its major social effect was to replace optimism with paranoia, which is Kryptonite to Kennedyism. Even the allegedly optimistic and sunny Reagan was really a Bizarro World Kennedy whose offering to Americans was not anything new and heroic but instead What Was Rightfully Theirs taken back from the machine pols and minorities who had stolen it from them, and not moon shots but the Strategic Defense Initiative. (Trump dropped the smiley-face façade but his approach is absolutely the same as Reagan’s otherwise.)

And the Kennedy legacy also came under more direct attack — not mainly by Republicans, who had no political reason to assail a martyred president, but rather by wiseguy liberals and leftists who were embarrassed by it.

Part of it was Ted Kennedy and Chappaquiddick — you could hardly design a more effective death-strike to the Kennedy mystique than the fecklessness and cowardice of that event; when the outrage died down, Ted and the remaining Kennedy family became a punchline for the National Lampoon/SNL generation. Republicans had always sneered among themselves at the Kennedys, but now many Democrats did too — maybe more so, out of embarrassment for having believed in the first place.

Soon enough that contempt got reverse-engineered onto Jack, too. A lot of young, erstwhile idealist supporters could no longer ignore that Camelot was as much a stage production as the musical from which it got its name. We began to think about Jack’s caddishness and political trimming, and Bobby’s work for Joe McCarthy. Sure, some old people still believed in Kennedyism even as they lost faith in the Democrats; for years Republicans like Jack Kemp claimed Kennedyism for themselves in their rhetoric and personal grooming. But for idealists turned cynics — as many of us were, in the 70s and after — it was just a con for the rubes we used to be. (And it’s still going on, QED.)

Last week I dropped by the Kennedy Center to take in the exhibit they just opened, “Art and Ideals: President John F. Kennedy,” in conjunction with the institution’s COVID-delayed 50th Anniversary celebrations. Though it has some touches of modern museology — cross-cutting screens and interactive features (like a “dynamic portraiture” thing where you can get an AI-generated portrait of yourself in the manner of Elaine de Kooning’s of JFK) — it is very retro in its whole-hog Kennedyist perspective. After decades of revision, it’s kind of a shock.

There’s no skeptical reexamination in this exhibit. There’s nothing about bootlegger Joe Kennedy grooming his eldest for the presidency and, when Joe Jr. died, laying it all on Jack; nothing about JFK’s hushed-up Addison’s Disease or his affairs or who really wrote “Profiles in Courage.”

Instead there’s some coverage of JFK’s shortened presidency, focused on civil rights, the space race, and inspirational oratory, and a lot about his and his wife’s arts outreach: cultural exchange, “jazz ambassadors,” Young People’s Concerts, Robert Frost, Pablo Casals.

It turns out – had I forgotten, or never known? –that Kennedy’s aesthetic and historical citations, whether or not he was coached in them by Sorensen and Schlesinger, are very good. He had a feel for classical influences and cited them, which is literally unthinkable now. I was reminded that JFK’s famous “Ich bin ein Berliner” line, for example, was prefaced by “two thousand years ago, the proudest boast was civis romanus sum.” And get a load of this:

But Goethe tells us in his greatest poem that Faust lost the liberty of his soul when he said to the passing moment: “Stay, thou art so fair.” And our liberty, too, is endangered if we pause for the passing moment, if we rest on our achievements, if we resist the pace of progress. For time and the world do not stand still. Change is the law of life. And those who look only to the past or the present are certain to miss the future.

OK, the “liberty of his soul” is a bit of a stretch, but the main thing is JFK drew a respectable analogy — which suggests that statesmanship, like education, should encourage the auditor to expend some effort to reach the thinking of the speaker, instead of just allowing himself to be pummeled or stroked by his words. (Also, the passage is a lesson in the use of cadence.)

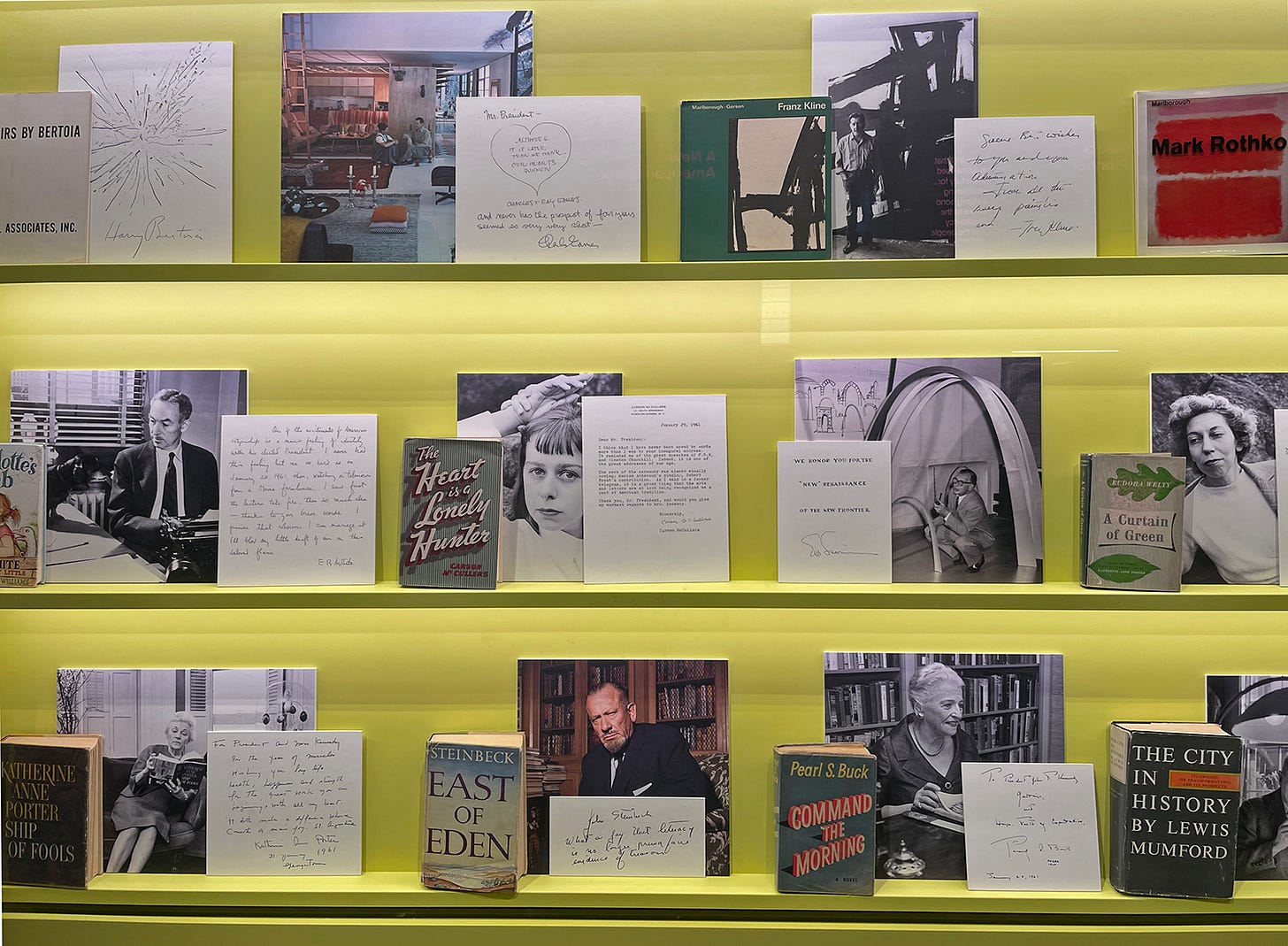

American artists responded well to JFK, as a vitrine full of their letters of appreciation to him demonstrates. Kennedy stroked them, which artists always like, but it’s hard to imagine someone like E.B. White or Carson McCullers, for example, going as fulsome as McCullers in particular did (“I think that I have never been moved by words more than I was by your inaugural address. It reminded me of the great speeches of F.D.R. and Winston Churchill…”) to lobby for a future dust-jacket blurb. I think rather the artists reacted to simply being respected — another unthinkable thing in the current climate — and had a justifiable sense that the president shared their values.

Maybe my reaction is informed by that, too. Or I can look at it the other way around: I became an artist and a writer not only because it’s fun to do but also because I respect the humanities, and I think it’s better to have leaders who also respect them, because such people are less likely to accelerate our current descent into bullshit and, who knows, may even hit the brakes. Like the man said, the age of Pericles was also the age of Phidias. And so what if JFK’s administration had a lot of drawbacks — Pericles wasn’t all that, either. Plus, in light of where we’ve gotten since, though there are no Kennedys on the scene I’d be willing to support, I’m now a lot more inclined than I was to indulge a little Kennedyism.

Kennedy may have been coached or scripted, but his oratory and rhetoric were truly a projection of America at its best. An America that, at least on the surface, was engaged in uplifting the world.

Contrast any Kennedy speech with anything uttered by, say, Dubya. Trump, of course, is an incoherent imbecile. Even Biden's speeches are not even pale comparisons to even the most banal Kennedy speech. (Of course, it didn't hurt that Kennedy was also quite witty and quick on his feet. The classic being when he presented Alan Shepard with a medal and he dropped the medal before giving it to Shepard. " . . . and this decoration, which is going from the ground up.")

Really interesting, thanks Roy. I can confirm that growing up working class in the Bronx in the late 60’s-70’s and living in an extended family situation, in our kitchen we had framed photos of the Pope, JFK, and more atypically, Walter Reuther (the UAW President) with MLK, Jr. – my father and grandfather were both UAW men and my grandfather was quite the socialist/commie type.

In talking about cults of personality, I can understand JFK and even, although I disagreed with his politics, Reagan being cult figures. But seven years later it still boggles my mind how Trump attained that status. Truly, we are in Idiocracy.