I had a funny idea for this issue — lots of satirical provender in the news lately, god knows! — but instead I’m going to write about James Chance, who just passed. My heart is full, not on account of auld acquaintance — I never knew the man, not that I would impose on you good people for some maudlin private in-mem if I did — but for the weird, rough enchantment he put into the world and my life.

Yesterday Willie Mays and Anouk Aimée went, too, and as Glenn Kenny notes that is indeed an “unusually ECLECTIC cultural erasure.” In a way, especially considering that Aimée and Mays reached ripe ages, it’s a positive thing: Gaze upon the broad treasures of Western Civ! Chance, though, I heard had been sick, and for a while when I saw clips of him performing he was singing and playing keyboards rather than sax, suggesting a paucity of wind. 71 years wasn’t enough.

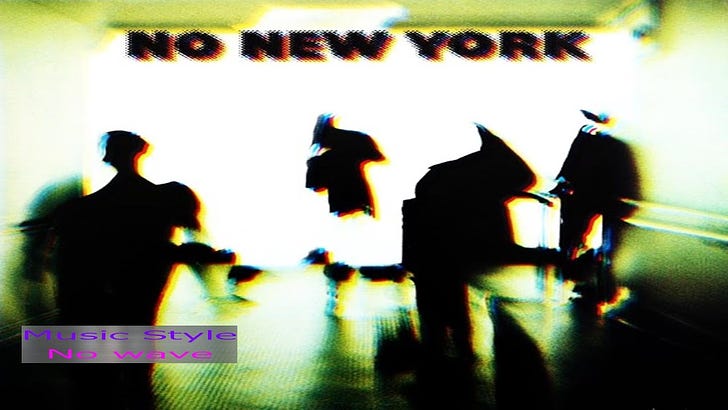

But this is about something he did long ago. Some of you know James Chance and the Contortions at least as well as I do, and the No New York compilation Brian Eno made and on which they played. That’s a hell of a record, but the Contortions stand out, in part because of the room-mic’d, live-in-studio recording for which, the story goes, Chance fought Eno and won (and which the engineers beautifully captured).

Give a little listen. Back in that era there was a lot of stuff running in the punk rock sluice that one might call fake jazz. Several bands playing the troglodyte circuit did dramatic chromatic runs over their rhythm sections instead of power chords. Sometimes they dressed fancy to show they weren’t scared by us savages, and some of them hemi-demi-semi made it. Like the Lounge Lizards. Apart from indie cred, they weren’t too different from any other crew of conservatory geeks. But they always had at least one foot in the accepted downtown establishment, and you still see John Lurie on fringe cable shows today, working the quirk.

Chance, out of Milwaukee, was not aimed at such a destiny. (Maybe he thought he was, who knows? But nothing in his career suggests it.) When I saw him and the Contortions in the late 70s they were, as that No New York clip suggests, tight, angular, and aggressive. Chance sometimes wore dinner jackets but instead of jazz affectations the Contortions had real show-band chops: They were good on their instruments but better on listening — preternaturally following the ebb and flow and stops and starts of their colleagues’ playing and whatever the leader called for.

This became especially important because Chance had a shtick back then that required heightened awareness all around: He would go into the audience and get actually physically aggressive with the audience. I’m not sure how he first got into this, but I recall the first time I experienced it — I think at the Paradise Garage on a Richard Hell and the Voidoids bill. It was a playful energy exchange with the super wised-up crowd: He’d hurl himself into the audience and they would roll off him or cheerfully shove back. Chance affected anger at this — WHY DON’T YOU FIGHT ME, he yelled at one point — but the crowd knew better.

I went mad for this and went to see him, God, I think a dozen times. Every show was different. (The band was always exemplary, and Adele Bertei is still my all-time favorite organ player next to E. Power Biggs.) And the difference from show to show, to an extraordinary degree, had to do with the audience.

For instance, at one show at Max’s, the crowd was primed like the Paradise Garage crowd, except in a strangely fan-boyish way — in fact a guy from Philly at my table kept saying “I hope he hits me” and when Chance, perhaps sensing this, flew off the stage, grabbed him by the nose and shoved his head back, the guy was ecstatic. (The top-billed band that night, by the way, making what I believe was their New York debut, was X. They were OK.) At another show at CBGBs, Chance went into the crowd and gave one gigantic normie-looking guy a hard time, play-slapping him, and the guy physically picked Chance up and dumped him back on the stage. The look of admiration on Chance’s face was magnificent.

Sometimes, though, the auditors just didn’t get it. One very bad scene was a CBs show that Wire (!) was supposed to play but cancelled. Chance was called to fill in, and it became quickly apparent that most of the crowd was neither familiar with nor into his act. People yelled in outrage, swung on him, called for the management. After about a half-hour of this Chance drained a tumbler of something, threw it on the stage and smashed it, threw himself on the stage and rolled in the broken glass, then stood up with blood streaming down his forehead and announced I’M NOT SACRIFICING MYSELF FOR YOU ANYMORE and left.

And I have to mention one of those weekdays back then at Max’s when Johnny Thunders and his buddies were jamming for coin — I used to go to those out of admiration and boredom — and Chance, in a tieless suit and sporting a black eye, unexpectedly stormed the stage and refused to leave unless he was allowed to sing “Route 66.” There was a minute or so of chaos and I think at one point Walter Lure slugged him, but they finally let him do it; he seemed pleased, like a bum who got a nice blanket, and at the end toppled off the stage and was gone.

Now, despite my punkrock pedigree, it’s not the violence or crudity of these incidents that makes them memorable to me — it’s the responsiveness of the artist to his environment. And it occurs to me now that, along with his musical achievements with the Contortions, Chance successfully accomplished something that many performers, particularly of the avant-garde sort, try to do, or say they’re trying to do: He let himself be alive to the situation, to the possibilities of every performance. It was the opposite of the ancient idea, in other words, of doing it exactly the same way every time. That is to say, it was jazz — and not the fake kind.

I didn’t play his kind of music, but I was inspired by what he did, and whenever I try to plumb the deep, dark well all this stuff comes from I follow his example. RIP.

(By the way, happy Juneteenth! I recommend this excellent related post by Yastreblyansky.)

I come here everyday because something inside of me craves dynamic juxtapositions like Richard Hell and E.Power Biggs . I don't envy many people, I got it good and I'm lucky enough to realize it, but man, I envy the shit out of your New York punk scene experience. Closest I ever got was seeing Talking Heads in 78 and Richard Quine play with Lou Reed in 84. That was at the Agoria Cleveland

Yaz is a great writer.

He deserves wider exposure

I'm so glad that Willie got to see the Negro League stats rolled into MLB and Josh Gibson can assume his rightful mantle as the best hitter in baseball PERIOD FULL STOP. It's like Willie was thinking, "well, now my work here is done.

And baseball fan or no, if you've never seen The Catch, well, prepare to be amazed.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yTSGIy8HXnc