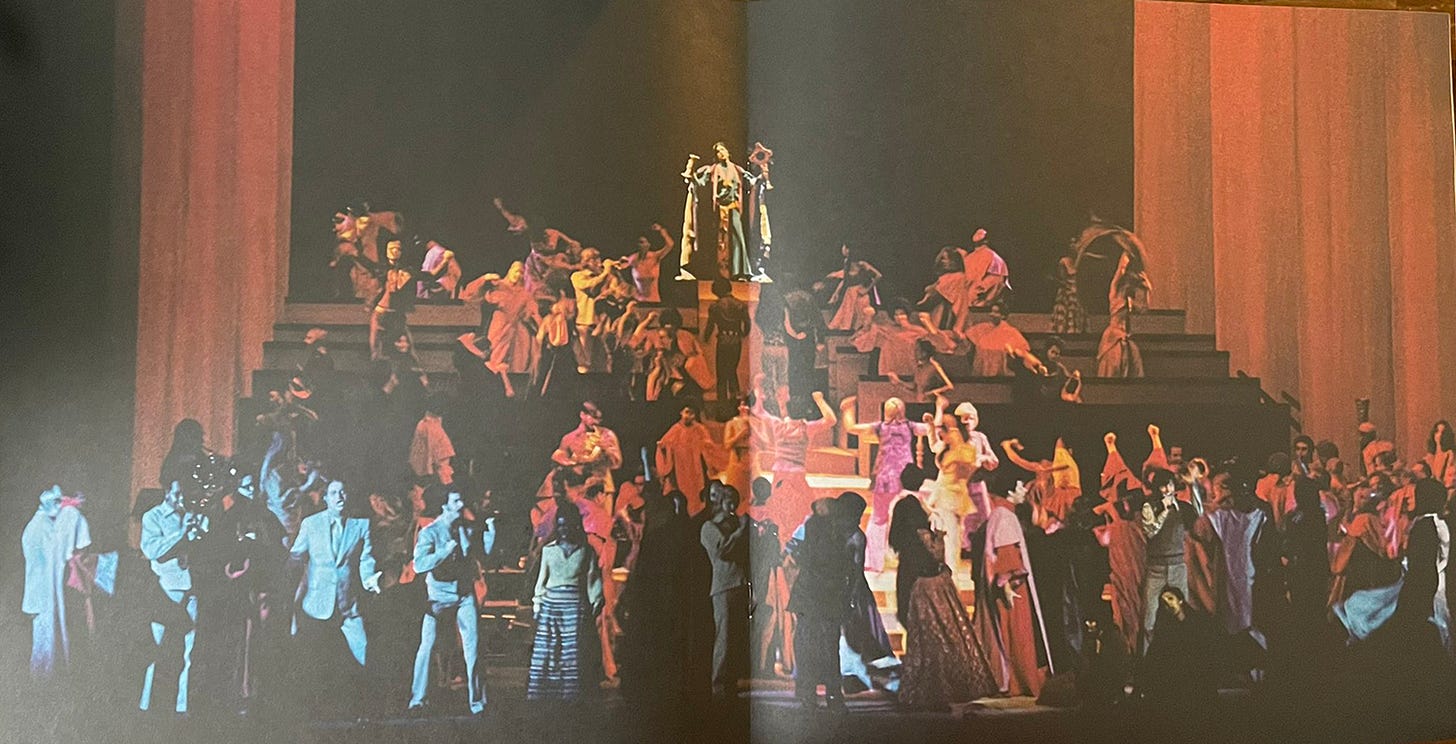

(From the original 1971 soundtrack album. No, I will not flatten it more for a better reproduction!)

When I was a kid we knew this family of Polish Catholics who still adhered to the lunch-bucket Democratic politics of that era, which I think is mainly why they had a record of the show that had just opened the new Kennedy Center in Washington in 1971: Leonard Bernstein’s Mass. I don’t think they listened to it much.

But I was enraptured — by the music, for one thing, which swung through multiple styles including Broadway, sacred classical, modern classical, and what Bernstein and his baby co-librettist Stephen Schwartz (yeah, the Godspell guy) took for late-60s pop; but also the concept, which was to alternate the liturgical elements of a Latin Mass (processional, offertory, etc.) with the congregants’ growing expressions of doubt and alienation, and their disaffection at the Church’s inability to address these, turning into rage and driving “The Celebrant” to a breakdown and leading finally to a do-over in which the Mass returns to its original mission (and the Mass to its opening “A Simple Song”) and the reunion of the congregation.

The liturgical music was interesting, but the songs on both sides were all the glory. These guys were songwriters to their bones and even the hipness-inflections of the protesting, importuning plebes hit their marks:

And then a plaster God like you

Has the gall to tell me what to do

To become a man

To show my respect on my knees

Go genuflect, but don’t expect guarantees

Oh, just play it dumb

Play it blind

But when I go

Then

Will I become a god again?

Even today critics feel obliged to sniff at this at dated, but it ain’t; the argot all survives and its use is poetic and assured. In fact the lyrics that cleave most obviously to the social issues of the era (the environment, militarism) are most thoroughly contemporary, for reasons that should be obvious:

God made us the boss

God gave us the cross

We turned it into a sword

To spread the Word of the Lord

We use His holy decrees

To do whatever we please

And it was good, yeah!

And it was goddamn good!

Bernstein’s idea of the new pop may have been second-hand, but it produced songs you can still enjoy. And the “Agnus Dei,” the song of the final outrage (“Give us peace now and we don’t mean later/Don’t forget You were once our Creator”), is rock and roll — not in form but in feeling. Really.

And though The Celebrant has to do a lot of Latin liturgy until his big diva breakdown, his songs of devotion and praise are as grand and soul-swelling as religious music is supposed to be:

O you people of power, your hour is now

You may plan to rule forever, but you never

Do somehow

So we wait in silent treason until reason is

Restored

And we wait for the season of the Word of

The Lord

I was a working-class Catholic boy with artistic ambitions so naturally I swooned over this. But the world at large rejected the thing as an offensive and ill-conceived pastiche — which over time made me love it more, not a little perversely: I got a kick out of the idea of all those Washington nobs coming to the new Kennedy Center in their wide-lapel tuxedos and organdy gowns and getting a load of these two Jews telling them where the One Holy Catholic & Apostolic went wrong. (Cut to the out-of-town preview scene in The Bandwagon: “Drive me to the station, maybe I can still make the 11:40 to New York!”).

But over time, I came to accept that maybe, sweet as the tunes were, Mass really wasn’t so thoroughly baked, and that I had been reacting to the ambition rather than to accomplishment of it. While as music, it built nicely, I could see where the structure of the dramatic argument — the crowd’s dissension against the Celebrant’s insistence, the collapse and rebirth — was kind of flimsy.

For example, whence do the complaints originate? There are references to the problems the Church isn’t able to help, like sexual confusion, that might be explained, one guesses, simply by The Times In Which We Live/Were Living, but not, alas, in the text. And why does that all build up to insurrection rather than to abandonment — as, in the West, it actually does?

Maybe a strong stage production could show a way out of that. But when was I ever going to see one? (I missed Marin Alsop’s in Baltimore — any of you catch it?)

Then the 50th Anniversary production of the Mass came to the Kennedy Center. I saw it Saturday night. Throughout, I had a strong sentimental reaction — grateful tears, mostly, at finally seeing the object of my affection in lush raiment: full, indeed lavish staging with by my count at least 50 singers and dancers, a choir of 40 up by the Concert Hall organ pipes, and the full Washington Symphony Orchestra upstage (four bull fiddles!).

But I also responded to the Mass itself. And if director Alison Moritz’s and choreographer Hope Boykin’s version didn’t thoroughly solve the problems, it made them easy to overlook.

The feeling of uplift and community at the beginning, for example — buoyed by the inclusion of an expertly-directed group of happy children (you can’t go wrong with that!) — showed the promise of the Church and its appeal, and made the later complaints of the disappointed congregants at the betrayal of that promise more understandable.

The congregation itself was vivid and sang well, and Moritz obviously put in some work to give everyone a little backstory — though, as usually happens when the authors don’t help, one became aware of the effort. The soloists among them had distinct if necessarily broad character traits — egoist, firebrand, disappointed wife, frustrated activist — that at least suggest reasons that could lead to the upheaval. (All good, but Nick Rashad Burroughs really punched the clock.) A corps of dancers dressed as The Celebrant’s acolytes reflected the moods in the show: Sometimes they wheeled, smooth and jubilant; sometimes they were cramped in loops of frustration. They dressed the stage but weren’t vital.

A big choice was making The Celebrant tortured from the beginning; in fact he was found at rise groveling in a pew, to the extent that I worried an usher would pitch him out as a disturbed vagrant. His anguish seemed both personal — the old loss-of-faith thing — and a sympathetic response to the brewing restiveness of his flock.

I think that was overall a mistake; it made the uprising look like a response to his weakness, for one thing, rather than to the unresponsive authority that The Celebrant’s music suggests. And when we got to the “Things Get Broken” breakdown, there was no slap-in-the-face, sudden confrontation with what happens when all authority goes down; you could see that in the rather forced bafflement of the congregants who only a moment earlier had been literally rioting.

On the other hand, even in The Celebrant’s pain, baritone Will Liverman was absolutely at the right scale vocally and in his presence — that is, massive and sometimes majestic. Even when the idea he was enacting was wrong, his voice was right.

Maybe the big thing was that it worked, and at the end the crowd went nuts for it, with standing o’s and roars (and, unlike on poor old Broadway, there are very few spectators in any Kennedy Center audience who feel they have to stand and yell to feel like they got their money’s worth). It was big for me, anyway. Mass is not, it turns out, a badly dated quasi-religious artifact like Auden’s Song of the Devil or MacLeish’s J.B.; it lives, it sings. And maybe now we’ll start seeing it around more.

It helps to remember that Vatican II was part of the backdrop of this. For the first time in millennia, the Church was trying to update and address the concerns of congregants. The results pleased few and pissed off many. Those who wanted reform and update were pissed that it did not go far enough. And, of course, those who were against reform went into instant backlash mode.

Also in the background: The smashed hopes of the '60s. From JFK's assassination to RFK's assassination to MLK's assassination to the constant carnage of Viet Nam to the rise of Nixon, everywhere one looked, hope was dying and faith was being trampled by reality.

So if Mass seems a bit confused with an ending that doesn't seem to fit, I think it's more a reflection of what was going on at the time than any fault of its creators.

Thanks for the terrific review. I was taking a music class back then when someone walked in with the score -- IIRC (not a sure thing at my age) it was immense, with an all black cover with "Mass" written in gold gothic lettering, like a new Bible of sorts. The actual music students gathered around the piano to play through it and marvel. Being a hipster rock and roller, I thought this was decidedly uncool, and left them to their study. I've since appreciated bits of the thing over the years, and your review, as all good reviews should, makes me want to go listen to it with a more open mind, which I didn't want to do when it premiered.